This is a series on research about technology and business. It is offered as a toolkit for those undertaking tech research, or considering the purchase of research services; the focus is almost entirely on qualitative research, not statistical research.

In the first article, I introduced the concept of mapping your business against the research services. This article is a report from the field on the services, strengths, and shortcomings of the major research firms I’ve dealt with. In articles to come, we’ll think of research in its broader context as an ongoing learning exercise, and I’ll expand on the idea of research portfolios that include sources beyond the major firms.

What big research firms have in common

For the companies mentioned here, there is a core business model:

- Annual contracts for "seats" granting web access to (mostly) written reports, based on the original work of analysts in the employ of the firm. In general, that intellectual property represents the value that customers pay for.

- The one thing I most wanted to buy from research companies was an enterprise license, in which anyone within my company could access the products of the research companies. None of them will sell you that license. IDC and Forrester allow dynamic reassignment of the licensed seats during the contract year, which partly offsets that limitation. Forrester also allows reassignment of its extra-cost Leadership Board seats, which I found to be especially valuable.

- Your ongoing contact with the company will be through a client team: almost always composed of someone from sales who is the feet-on-the-ground in-person contact, plus an internal resource with more direct access to the analysts.

- You will be strongly discouraged from contacting analysts directly, even once you know them from previous experience with their work, although every firm has a process for requesting telephone meetings with analysts. Depending on the license model you purchase, you may have a fixed or an unlimited number of those calls at your disposal. The controlled access is part of the intellectual property the firms sell you.

- Once you engage the company often enough on a specific topic or request, or pass a certain level of engagement with one team or analyst, the companies may decide that goes beyond the bounds of your contract terms and has become a “special service,” for which you will pay separately.

- Companies sell some services “pre-customized” to serve interests by role (very common right now), or by vertical industry. It’s also common to hear research firms sounding like someone on a first date. If the interest you express while in the sales process is at all within the range of what that firm offers, they really, really want you to like them. You’re far more likely to hear “of course we’re experts in that field,” than “no, much as I’d like to tell you otherwise, our competitor X is better there.”

- For that reason, I advocate buying a portfolio of research products if you can, and part of the value I offer is help from outside to make that process smarter and more informed. This is becoming a smaller field to choose from as acquisitions by the bigger companies have ended the separate existence of some well-known brands.

The companies also typically expose some of their knowledge capital through conferences, some huge and “everything including the kitchen sink,” like the Gartner Symposium, some specialized, like Forrester’s Enterprise Architecture Forum. It’s not unusual to find walls around some part of the content sold by the big firms, for which you have to add another service to your contract; these are usually around some form of data--especially benchmarking data--gathered in the process of their research work.

What the research companies are NOT:

- Although the big consulting firms like Accenture, BearingPoint, or Deloitte also maintain large numbers of their own research analysts, they have a limited overlap with firms like IDC and Forrester. Consultants are more likely to give specific, one-off advice, and then offer you the opportunity to pay them to help you take action on their recommendations.

- The work of research companies is not like that of academic institutions. There is internal peer review, but the value proposition of big research firms also includes a consistent point of view across different specializations. They are driven by what they can sell, and they are commercial institutions. That is not a bad thing, but I recommend that you always view the value of commercial research reports through the same critical lens you would use for the products you buy from any vendor.

- In the same vein, star analysts--those who really excel in thought leadership and new ideas--may self-select out of the corporate research model. There are great minds working for Gartner and its competitors, but there are many others outside that business model. Some of the best analysts I know of are former employees of the big firms, now operating privately or as part of boutique research firms.

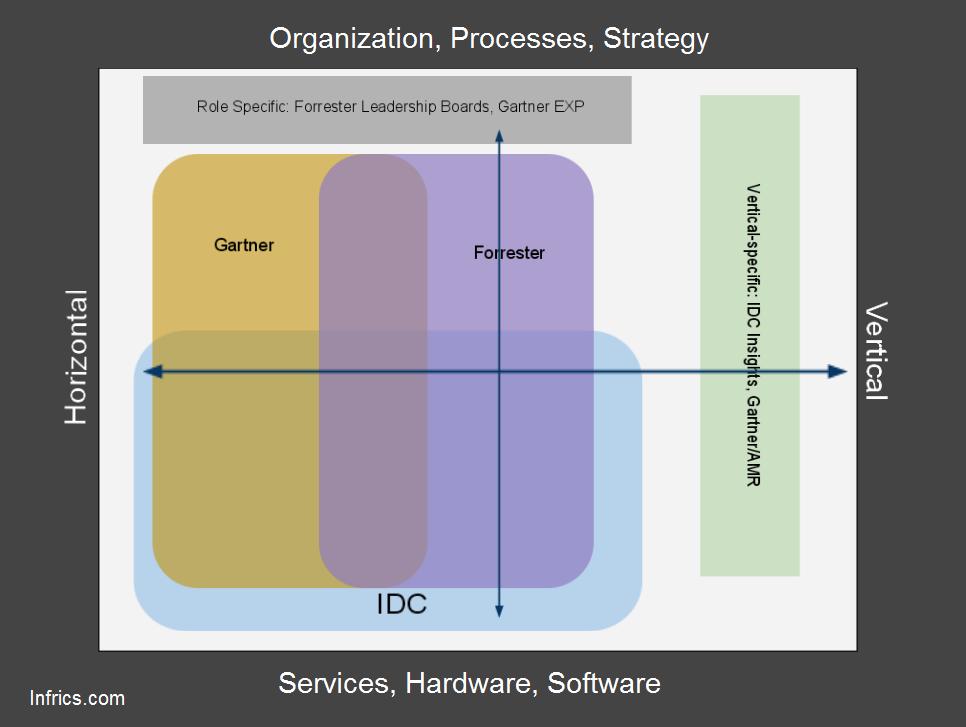

Here is the map of research companies value, plotted against horizontal/vertical, and strategic/tactical

Thinking about the big 3: Gartner, Forrester, and IDC

These comments are both a report of my own experiences over 10 years as a client, and my opinions about the strengths and weaknesses of the companies. But remember, if one of them fits a specific need or pattern based on your own business/research mapping, that can heavily influence what I report.

Although I’ve mostly had all three of the companies in my research portfolio, there is only one that has ALWAYS been there without fail:

IDC

Thinking about the big 3: Gartner, Forrester, and IDC

These comments are both a report of my own experiences over 10 years as a client, and my opinions about the strengths and weaknesses of the companies. But remember, if one of them fits a specific need or pattern based on your own business/research mapping, that can heavily influence what I report.

Although I’ve mostly had all three of the companies in my research portfolio, there is only one that has ALWAYS been there without fail:

IDC

What they offer: IDC is the research arm of the IDG group of companies, publisher of tech magazines like Mac World, Network World, and CIO. They have over 1000 analysts distributed all over the world. IDC is 47 years old; its focus is strongly data-oriented around business metrics like market share, volume of sales, and growth predictions. IDC’s traditional client base is the companies that make and sell technology-related products and services, although that has grown somewhat over the years to include more for the people who buy and implement those products. Vertical Insights offers specific services in Manufacturing, Retail, Financial, Healthcare, Energy, and Government. A benchmarking service is sold separately for pricing of equipment like laptops, desktops, and servers.

What I like: IDC is without peer for maintaining personal customer service despite being a large company. I had relationships with both sales and internal client service that spanned years; alone among the big three, IDC could get me answers within hours to help with an urgent request from the CIO. IDC often pulled specific data from unpublished research for me upon request, allowing me to send my internal clients a chart or Excel sheet that answered their questions in ways not available through a website search.

IDC’s sales and intellectual property model is the most flexible of the three companies. The company philosophy seems to be “the more people who see our work, the better our sales prospects will be,” so they allowed me share any reports freely, and to post IDC reports to our corporate intranet (which neither Gartner nor Forrester will allow, or even negotiate as a contract element). IDC’s contracts are generous with seats, relatively unrestricted in terms of who can request analyst calls, and are based on a concept called service units. Every year brought a bank of these units which could be “spent” for analyst time, reports that were not part of the master agreement, or for any other custom work. Gartner will not do that, and Forrester will, but only by special request.

In terms of content, IDC has far and away the best global reach. If I needed a report on an HR software firm in Poland, or comparisons of ERP vendor market shares in China, IDC was my go-to answer every time. Although Gartner sells data about tech spend and market share under its Dataquest brand, I never once felt the need to purchase it because of the wealth of data included in my IDC contract as part of the base price.

The IDC Directions conference, held every year in silicon valley and Boston, has consistently been one of the highest-value one-day tech events I’ve ever attended.

Problems/limitations: IDC is not the place to turn for a report on best practices, for an RFP template, or a study on IT organization. IDC can tell you a lot about the tech companies' market shares, but does little in the way of vendor comparisons. Those are not part of their core strength, although I believe from talks with IDC that an effort is being considered to extend that part of their offering, which may put them in more direct competition with Gartner and Forrester. IDC is an excellent--for me, indispensable--companion to either Forrester or Gartner, but there are few cases where it would work as the sole research buy.

The IDC website and search interface for users has been the worst of the three companies for years. The design and graphics of their reports tend to be unimaginative, but they are very rich in useful graphs and charts. IDC has never done conferences longer than one day very well, and have mostly abandoned the concept.

Forrester

What they offer: Forrester is the smallest of the three firms discussed here, but they compete in the big research firm space, oftentimes being best-of-breed for their specialized expertise. Forrester has not chosen to compete in a big way in the market for data about tech sales and market share, but rather to be a thought leader in a couple of major areas: the philosophy of IT and business (reflected in a company-wide push going on for several years now to relabel “IT” as “BT,” Business Technology.) Forrester’s other major focus is marketing, e-commerce, and social networking--a choice which places the company very well for the current needs of the research market.

Forrester’s delivery and sales model is based around IT roles like CIO, Enterprise Architecture, Sourcing, and Knowledge Management. They sell both role-specific regular access seats as well as “Leadership Board” seats with facilitated peer interactions, a dedicated client services representative, and “elite traveler” perks such as dedicated lounges at conferences.

What I like: Forrester’s focus on marketing and social networking is currently the best among their big-research peer group. The Consumer Technographics surveys and reports are the most complete insight into online behavior, and are especially well structured to allow drill-downs by demographic and behavior style. They sell some of the marketing expertise separately to non-IT parts of businesses, but there is considerable overlap. Forrester was the most useful research partner I had when talking to business strategists. If you are very highly focused on web, social, and e-commerce, you could manage with Forrester alone.

Forrester’s Wave product, their graphical vendor comparison tool, is similar in approach to the well-known Gartner Magic Quadrant. However, the wave lets end users change relative weights of the comparison criteria by downloading and interacting with an Excel spreadsheet, resulting in a graphical display customized for the specific need--a very cool enhancement. Forrester is not as prolific with Wave reports as Gartner is with MQs, but where they exist for the products you’re investigating, points go to Forrester.

In general, Forrester’s analyst team seems very engaged with customers, and there are some truly excellent individuals: Claire Schooley in e-learning and HR. Randy Heffner in SOA, web infrastructure, and Enterprise Architecture. Paul Hamerman in applications, ERP, business process. Forrester’s 3-day Forum event, held every spring in the western US (usually Las Vegas,) is a very worthwhile conference, with great breadth of topics, but not the intensity of crowds and packed agendas you find at the Gartner Symposium.

Problems/limitations: Forrester is not likely your best choice if you’re about to do an end-to-end overhaul of your data center, or other highly infrastructure-oriented tasks. Their work tends to be more North America focused, especially when compared with the global presence of IDC; within the last 2 years I have seen more international reports from their technographics series (to get full access to all technographics reports, you must purchase a separate option as part of your contract, but many of them are included in the basic access plans.) Among the role-specific options I’ve considered or purchased, both the CIO and the Sourcing Leadership boards were strong offerings, although in general, my internal clients found the Gartner offering on Enterprise Architecture stronger than Forrester’s. More on this in the Gartner commentary.

Forrester can get overly wrapped up in its own hype about an internal catchphrase like Business Technology, and I have sensed a “blinder effect” there, in which it appears as if there had been a corporate decision to include that concept in as many reports and engagements as possible. This syndrome pops up a lot in the world of research-as-a-business, as companies jockey for market position based on their advocacy of their own ideas or buzzwords.

Forrester seems to experience churn in its sales force more often than either Gartner or IDC, and it shows in customer service--midpack between IDC at the top and Gartner on the other side. This is an often-overlooked part of the research relationship; the sales rep is your primary interface with the value you are paying for. Good ones, and good companies, invest a lot of time in that relationship, and so do you. Lose that rep, and much of that time he or she spent understanding your needs is gone. The burden then falls on you to educate the replacement. This is compounded by the fact that none of the three companies has a very good internal CRM system to maintain that customer knowledge, or to enable a company-wide end-to-end view of the work you undertake together. I will say that Forrester has gotten much better here in recent years, but I’d recommend that one of the questions you ask of any company is, “what is the average tenure of your sales team with specific clients?”

Gartner

What they offer: Gartner is a large, multipurpose research firm, very highly commercialized, and of the three, it is the one that comes closest to providing value to almost every aspect of the enterprise. They also use a system of role segmentation for value delivery, selling a variety of access seats at different price points and with different combinations of access and specialization.

There are separate offerings around data--IT benchmarking and reports on market share, spend, and size--plus a contract review and negotiation service, role-based coaching and peer network facilitation, and a very active conference division. The Gartner Symposium, held in several cities around the world each year, draws about 10,000 attendees to the biggest venue, every October at Disney World in Orlando. In typical Gartner fashion, they bill it as “the world’s most important gathering of CIOs and senior IT executives.”

What I like: The breadth of coverage Gartner offers is a big plus for them; further, within a corporate IT organization, most people have been exposed to Gartner’s work before. There is a certain comfort in going to a meeting and saying, “Gartner says this about that,” although in my opinion, the Gartner view is not always the best one, nor the most complete. And the company does some excellent work, including some good heavy lifting around product evaluations and some of their reports on best practices. For many best practice areas, Gartner offers "toolkits," .zip file compilations of worksheets and checklists--an excellent, actionable addition to their research.

Gartner is smart about acquiring talent and specialization it does not already have in house; their acquisition of Meta Group at the end of 2004 dramatically filled out Gartner’s Enterprise Architecture offering, making them a leader in the field. Gartner had virtually no presence in the manufacturing vertical, leaving the field wide open to AMR and the IDC Manufacturing Insights practice, so they acquired AMR at the very end of 2009. According to Gartner’s own report, they have made 32 acquisitions since they went public in 1973.

Over the years, Gartner has alerted me to some genuinely important ideas that continue to influence my thinking to this day; they were the first of the big research firms to realize the importance of consumer technologies to the enterprise IT landscape. A 2006 Symposium presentation on “middle out architecture” by Nick Gall, who came to Gartner via the Meta acquisition, is one of the best works of thought leadership I’ve ever seen. Ditto with Hung LeHong’s “Goog-Azon: the Web 2.0 Monster That Will Devour Your Business Model,” a spot-on prediction about the evolution of mobile-device shopping augmentation through location, context, and search. Because of the sheer volume of output from Gartner, it takes diligence to sort out the truly useful from the boilerplate and the routine, both of which are also present in abundance in their work. Just be mindful.

Although I have serious reservations about the way Gartner does business (see below,) I still believe they are a very worthwhile part of a research portfolio. Where I recommended Forrester for social and e-business, if you had to go with just one company and were more toward the tactical/horizontal end of the research map, Gartner would be your logical choice.

Problems/limitations: In my opinion, the very real value of much of Gartner’s work is masked by the bad feelings engendered by their customer-facing operations. If there is one word I heard more often than any other about Gartner, it is “arrogant.”

There is no pleasure to be had in dealing with Gartner as a business; their sales approach is an order of magnitude more aggressive than either Forrester’s or IDC’s. The array of service offerings at contract time is overall less flexible than their competitors, and more restrictive than Forrester or IDC about intellectual property rights. I would frequently approach senior executives from the IT organizations I worked in about their experiences dealing with Gartner sales before I became the central point of contact. The most common reply: “Can you PLEASE keep them from bothering me?!”

Of the three companies discussed here, you really feel Gartner’s size, and not in a good way. The process of scheduling a call with an analyst is cumbersome; you must go through a scheduling office, which has no insight into the information you’ve shared with your customer service team, and frequently misfires matching analysts with your request. You can never expect nuance in a place where you most need someone who can say “I know just the person you should talk with.” Contrast this with IDC, where my internal rep scheduled appointments directly, actually talked with specific analysts about my questions before setting up appointments, and had little trouble putting me in touch with someone by phone within 24 hours if I had an urgent need.

Gartner’s web site has search restricted to only paid members, so you can’t even see titles of articles you are interested in without buying the service. Both IDC and Forrester have full public search enabled, with executive summaries of content, and the ability to purchase individual articles. I believe that ability is central to showing a company’s value to clients and prospects.

Gartner has different sales organizations in different parts of the world, and this became a serious problem for me in my last engagement with them. When I wanted a single global sales point of contact for all my Gartner dealings, they told me it was not possible.

Overall, in my opinion, Gartner would be a pretty great company if it only got out of its own way and worked harder on relationships and less on sales.

Summing up: If you are in business, the chances are good you will either be approached by one of these companies, or will consider them on your own as a resource. These insights may help you in the process. This topic is one where your comments are especially welcome. What has your own experience been like? Do you work for one of the firms, and would like to add to the content, or challenge any opinions?

For the last 10 years, I bought research products (primarily from Gartner, Forrester, AMR, and IDC) for a couple of major manufacturing firms: at the pre-purchase stage, I evaluated the research offerings and recommended a portfolio of research buys, then worked with their sales teams and our internal finance and legal departments on licensing and pricing. Post-purchase, I was the central point of contact between the firms and our internal clients, spending many hours each week on the companies’ websites, working with their customer service teams, and sitting in on many hundreds of calls with analysts. During that period I managed a total of nearly $2 million in research buys. I am available for phone, web conference, or in-person consultations about research planning. Although I clearly have a point of view, I have no commercial stake in the outcome of any plans or purchases you may make, just a lot of experience in the field.

Update, August 2012: Since this was published in the summer of 2011, I have been talking with people in the research business, and observing the emergence of some new research models that may threaten the value proposition of Garter, Forrester, and IDC. There are several articles on this idea:

New tech research models: threat to Gartner, Forrester. opportunity for you?

My, how you've changed: Technology research meets Social, Consumerization, Freemium

Next in the research series: Tech research without spending big bucks: four information streams for business

An Infrics.com business research consult day: money well spent