"No, NO, NO!! That is not what I want! Stop it!!" That's me, this past weekend, rushing to click "thumbs down" again, and increasingly frustrated with each bad choice suggested to me by Pandora.com. My situation: long-time enthusiast and Pandora user, multi-year payer of the annual $36 premium for ad-free Pandora One. Trying to create a new station called "Jazz Bistro with Piano," that would recreate the feeling of a small acoustic jazz club, good music for twilight on into a peaceful evening.

The reality: bumping over and over into Pandora's music choice algorithm, which can't understand what I want, and has no means by which I can tell it. After a while I had clicked "thumbs down" so many times I ran into the daily limit on skipped songs, so my custom radio station just stared at me blankly when I tried to give it feedback, one of those dreaded "computer says no" situations.

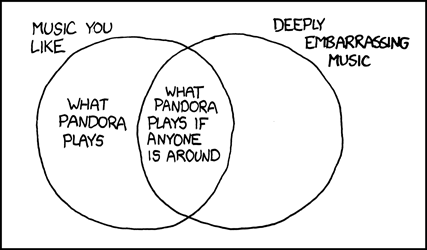

The state of personalization for ideas that involve personal taste, like music and movies has a long way to go. Right now, we could call it the era of "a little bit of you." Let's go into the Pandora experience and see this in action.

Example one: my "Indigo Girls" station is acoustic singer-songwriters, with a bit of preference for female artists. Besides the namesake duo, it's a natural place for artists like Carole King, James Taylor, and Laura Nyro. Also for Mary Chapin Carpenter, or so I thought; Pandora groups her with country artists, making her an outlier in my station, but still well within my taste. Alas, the result is an open door to all sorts of country music I don't want on this station, and no way to instruct the system that Ms. Carpenter appeals for other reasons. I like country music sometimes, but this station isn't where I want to hear it.

|

| Cartoon from xkcd.com |

Last year, Fast Company did a feature on Pandora's efforts to add social features, and to refine personalization. They quoted Chief Technology Officer Tom Conrad, who believes that "personalization is the foundation for the total product and user experience."

Here's the thing: it's just not that personalized yet. Pandora is very proud of its Music Genome Project, which seeks to identify metadata on millions of pieces of music, feeding the ability of the algorithm to find music you like. It's now added features to add input from others like you through the social tools. But the core of "music you like," your own feedback, is still remarkably coarse and of limited use. The general feeling Pandora's selection process offers is, "you're not really qualified to do something this advanced, but we are."

Pandora is a case where personalization has a good start, but with two steps, it can fully enter the era of you and give each user a richer experience. Not to mention, it can give Pandora a competitive edge against a raft of competitors in the music recommendation field.

--Let users specify the elements that are important to them: for my attempted Jazz Bistro station, it would include

- Jazz or jazz influence

- Acoustic

- solo or small ensemble

- Mix of vocal and instrumental pieces

- Some specific artists of my choice: like the Claude Bolling example above, or Bobby Short, who is to me the ultimate jazz bistro artist.

--Use the Music Genome Project resources, but temper it with user input: When I went back to the Jazz Bistro station I've been trying to create, the first selection was by Nat King Cole. That's good, in general, his music is perfect. So I clicked, "why was this track selected" and got this: "Based on what you've told us so far, we're playing this track because it features swing elements, smooth vocals, romantic lyrics, an electric guitar solo and a piano solo." Right, as far as it goes, but I don't want electric guitar, especially a solo. Each time this dialog comes up, Pandora should let me thumbs down the characteristics that don't fit and thumbs up the ones that matter. It should also be heuristic to learn the common metadata elements that drive my choices for this station.

Extreme personalization can go the other way as well, into Pandora's own infrastructure and licensing models. Last year I discussed this in an article on new models of content ownership based on our emerging stateless future. The gist of it is this: if I pay once, anywhere, for a license for personal use of a song, video, book, or software, it is my right to consume it anywhere, at any time, on the device of my choosing. If I've ever bought James Taylor's "Fire and Rain," a Pandora micro-personalization subroutine should be able to poll my library of purchased works, and not pay a performance royalty to stream it to me. If giving me the best possible personal radio station is the external expression of the era of you, this model is its internal, enterprise expression.

I'm still trying to get my new station right, and ever-hopeful for the success of Pandora.com. They are so close to being great, and I'd much rather have the imperfect version of today than be tied to old-fashioned terrestrial radio. They just need to understand that personalization works best when you remember to involve the person at the deepest levels.

You can listen to the two stations I discussed: